A Framework to Measure AI Value in the Enterprise: From Industrial Engineering to Cognitive Productivity

Introduction: Why Measure AI Value?

As enterprises increasingly adopt AI to streamline internal workflows, a common challenge arises: how do they accurately measure its value? Broadly speaking, there are two ways that any tool can create value for a business:

- Additional revenue: AI-based products or services sold to customers

- Cost savings: productivity increases that allow a company to do more with less

For the purposes of this article, additional revenue from AI will apply only to use-cases that are sold to the customer, and not to AI use-cases that assist, enable, or even replace sales reps. Those use-cases will be handled under the broad category of “productivity enhancements”: AI use-cases that enable a business to get more done with less.

Because measuring top-line revenue is relatively straight-forward, this white paper will focus on measuring AI value from productivity enhancements, which constitute the majority of AI enhancements and use-cases that most businesses are deploying.

What are most organizations doing today? In reality, few are actually making an effort to rigorously measure the value they get from AI investments. Instead, they deploy a few AI use-cases, lay off 5% or 10% of a department, and claim their AI investments are helping them cut costs. It’s a narrative-driven approach that attempts to convince investors.

With trillions of dollars of AI investment planned over the next decade, it’s important to find a better way to measure value from AI use-cases.

This white paper introduces a clear, structured framework to define and measure AI-driven productivity and value in knowledge work, particularly in enterprise software environments.

Industrial Engineering: The Foundation of Productivity Measurement

Productivity is simply output per unit of input. In a manufacturing context, it is relatively simple and straight-forward to measure. Some common examples include:

- Plant-level Productivity: Cars produced per day

- Area-level Productivity: Cars produced per day per square-foot of factory space

- Labor Productivity: Cars produced per worker-shift

- Machine Tool Productivity: Units produced per machine-hour

- Energy Productivity: Units produced per kilowatt hour

In manufacturing, because the product is physical, it is easy to measure.

Notice in the above examples, there is very little variability in the numerator in the equation, but there is considerable variability in the denominator. In other words, the goal – the output – is somewhat fixed.

The inputs are more varied, so one goal in increasing productivity is to identify, isolate, and improve the productivity of each of the input variables.

We call this process industrial engineering.

Principles of Industrial Engineering

In industrial engineering, productivity is defined as:

Productivity: Output per unit of input – how efficiently resources such as labor, capital time, materials, and energy are converted into finished products

Industrial Engineering is the discipline concerned with designing, optimizing, and managing complex systems involving people, materials, equipment, information, and energy. Its ultimate goal is to maximize productivity and quality while minimizing waste, cost, and time. In short, industrial engineering seeks to achieve more output per unit of input.

In practice, industrial engineers typically act as the bridge between engineering and management, focusing on process design, workflow optimization, operations research, and continuous improvement.

Industrial engineering has its roots in the industrial revolution, when managers sought to establish systems to better coordinate how labor used machines. An early pioneer of the discipline was Frederick Taylor, who formalized the concept of “scientific management”. He used data, observation, and time studies to make improvements in the manufacturing process.

Concepts like operations research, ergonomics, and Six Sigma all have their roots in industrial engineering.

With nearly 200 years of history and refinement, industrial engineering is a potential gold mine when looking for principals to apply to measuring AI value. A few key principals include:

- Standardization of Work

- Define the best-known method and make it the standard

- Reduce variability, improve predictability, simplify training

- Time & Motion Studies

- Analyze tasks and break them into steps

- Measure how long each step takes & eliminate wasteful movements

- Theory of Constraints

- Find the single step limiting throughput (the bottleneck)

- Distribute work evenly across people and machines to unlock overall performance

- Workload and Ergonomic Optimization

- Design work to best fit human capabilities and reduce fatigue

- Statistical Process Control (SPC)

- Use data and control charts to monitor processes and detect variation

- Identify and fix problems early to maintain consistent quality

In the 1980s, as Japanese car manufacturers sought to challenge American car manufacturers, the Japanese developed their own industrial engineering systems, which are now considered part of the cannon of best practices.

- Lean Thinking: Eliminate “Muda” (waste)

- Focus on removing non-value adding activities

- 8 classic sources of waste:

- Defects

- Overproduction

- Waiting

- Non-utilized talent

- Transportation time

- Inventory

- Motion

- Extra processing

- Continuous Improvement (Kaizen)

- Always look for small, incremental improvements

- Empower frontline workers or teams to suggest changes

- 5-S System

- Keep work environments organized to reduce wasted time searching for tools or information

- Sort, Set in order, Shine, Standardize, Sustain

- Just-in-time

- Produce or deliver only what’s needed, when it’s needed, in the quantity needed

- Reduce inventory and prove flow

These industrial engineering concepts provide a great frame of mind to begin assessing how and where to deploy AI in a company to maximize value.

But, because knowledge work differs from manufacturing, there are challenges that must be addressed and considered.

Knowledge Work: The Next Frontier of Industrial Engineering

In knowledge work, the inputs and outputs are less tangible: attention, creativity, decision-making, information,and insight, which makes it more difficult and challenging to measure productivity in knowledge work.

Specifically, here are some of the challenges in directly translating industrial engineering principles to knowledge work:

- Intangible & Variable Output

- Unlike factory work, where output is easily quantifiable (ie, units produced), knowledge work results in complex, non-linear deliverables.

- Highly valuable contributions may take little time but deliver an outsized impact. One bug fix may take 50 hours, and another 5 minutes, but that says little about their value.

- Variability in Effort vs. Impact

- One programmer might spend a week restructuring an inefficient algorithm, reducing the lines of code from 1000 to 100, leading to massive performance gains.

- Another programmer might deliver 10,000 lines of code in that same week, but have little to no impact.

- Collaboration & Dependencies

- Because many knowledge work outputs depend on interaction and collaboration with others, it can be difficult to identify and capture bottlenecks.

- Measuring an individual’s contribution, or even a specific team or departments contribution, might not reflect how much value they delivered as part of the whole

- Cognitive Work is Non-Linear

- Breakthroughs and high-value work can be unpredictable. A programmer might struggle for days on a problem and then solve it in an hour. A marketer might produce 100 pieces of content, but get 90% of their results from only 1.

- Unlike manual labor or machine operations, it is often impossible to “see” the pace of cognitive work.

Because of these challenges, many organizations measure activity rather than value creation – itself an amorphous concept.

This is especially true as organizations grow larger in size.

Examples of activity that organizations track include hours worked, emails sent, up-time on Slack, “responsiveness” to messages, number of meetings, or reports delivered.

Cal Newport, author of Deep Work, has written extensively about these misguided efforts to measure busyness, which ends up reducing valuable output rather than improving it.

Without a structured framework for measuring valuable output, any effort to measure the value of AI will be misguided.

Because of these challenges, many organizations default to simplistic metrics like “hours saved” as a proxy for productivity. While intuitive, this approach often misses the broader picture of how AI improves output quality, decision-making speed, and overall leverage across teams.

It also fails to account for if those hours result in any tangible benefit to the business. 10,000 employees each saving an hour a week might add up to 10,000 hours per week saved – theoretically the equivalent of 5 additional full-time employees. But does it result in the company producing more per unit of input?

Without a more rigorous framework to measure output, the answer is likely “no”.

Bridging the Two: Applying Industrial Engineering Principles to Knowledge Work

The core insight of Industrial Engineering is that work can be observed, measured, improved, and optimized. While it is built on the tangible world of physical systems and manufacturing, the same concepts can be applied to knowledge systems and knowledge work: information flows, decision cycles, digital tools, and knowledge-work products.

Here is a table that attempts to show components of physical manufacturing and their knowledge work equivalent.

| Physical Manufacturing | Knowledge Work | Description |

| Raw Materials | Data & information | Inputs needed to create final product |

| Machine tools & equipment | Software & digital tools | Tools that provide leverage on human strength (manufacturing) & cognition (knowledge work) |

| Plant Workers | Knowledge Workers | Human labor skilled at using the tools needed to needed to produce final product |

| Product Line | Workflow | Series of steps where human labor uses tools to transform inputs into outputs |

| Factory Layout | IT Architecture | The landscape where humans use tools to transform inputs into outputs |

| Inventory | WIP Deliverables | Stored items awaiting the next stage of processing or final delivery |

| Product | Deliverable | The final output that customers pay for |

Similarly, we can create a mapping of how industrial engineering principals can apply to their knowledge-work analog.

| IE Principle | Knowledge Work Analog |

| Standardization of Work | Defining repeatable workflows, templates, or automation; creating consistent “best-known methods” for tasks like report generation, code review, or customer responses. Develop and constantly improve SOP’s. |

| Time & Motion Studies | Measuring time to complete cognitive workflows before and after AI deployment (e.g., proposal drafting time, report generation time). |

| Theory of Constraints | Identifying workflow bottlenecks: decision latency, approval loops, dependency handoffs; use tools like AI to eliminate them (e.g., automated QA, routing, or summarization). |

| Ergonomic Optimization | Designing cognitive ergonomics: reducing mental switching cost (between tasks and between tools) and context load through better UX/UI and task batching (all meetings on Mon-Tue, email/slack only at specified hours). |

| Statistical Process Control | Monitoring process stability in pipelines (e.g., ticket resolution rates, coding quality metrics, customer support SLAs) and tracking variance before and after tool deployment or process adjustments. |

| Lean Thinking / Muda | Eliminating wasteful cognitive work: unnecessary meetings, repetitive reporting, copy-paste tasks, Slack back-and-forth. |

| Kaizen / Continuous Improvement | Incremental automation: identify the most repetitive and time-consuming tasks for elimination or automation; incrementally eliminate repetitive manual work |

The AI Value Framework

With this context, we have the foundations needed to outline an AI Value Framework.

The purpose of this framework is to provide enterprises with a structured, quantitative, and repeatable way to measure the value of AI investments, particularly as they relate to productivity improvements in knowledge work.

While many organizations track “hours saved” or “costs reduced,” these metrics fail to capture the true productivity gains that AI enables: higher output quality, faster cycle times, and expanded leverage across teams.

The AI Value Framework treats productivity as an engineering discipline, breaking it into measurable layers, just as industrial engineers did with physical systems.

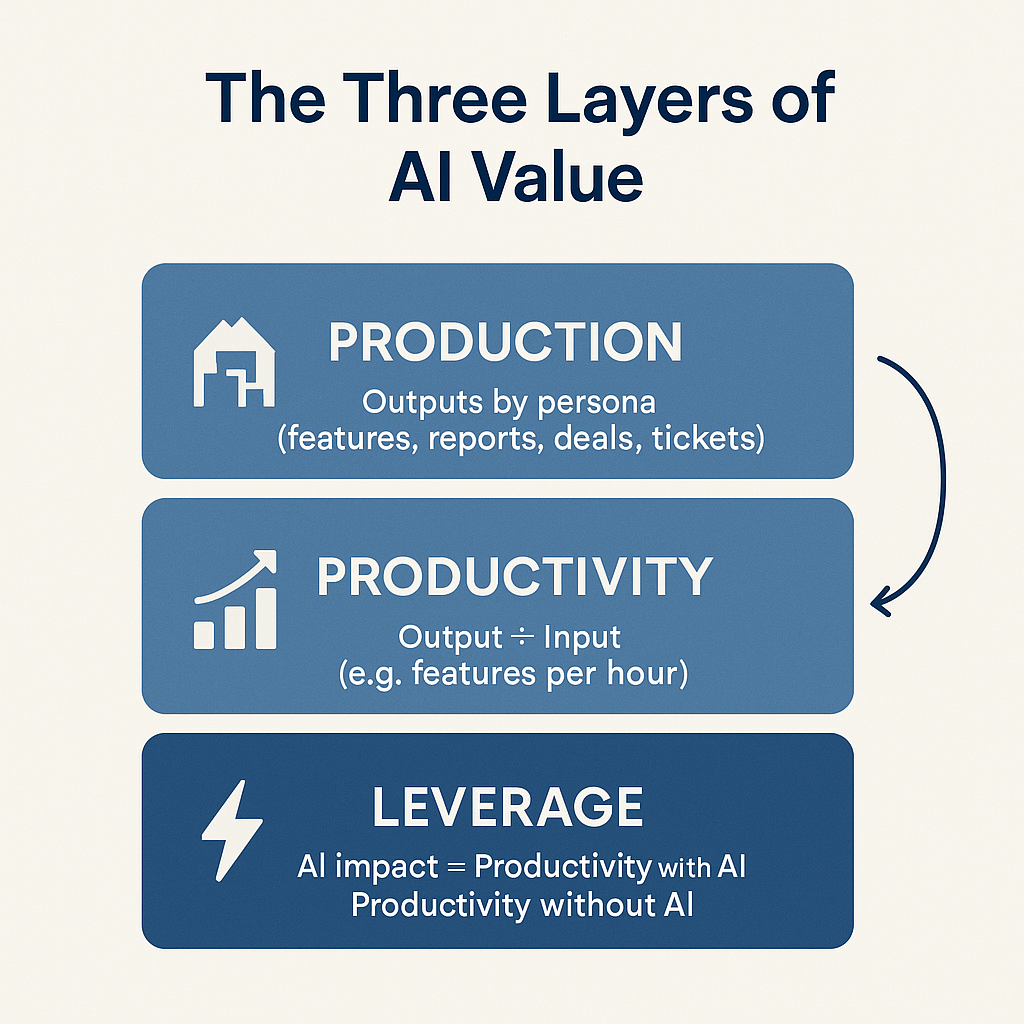

The Three Layers of AI Value

The framework can be visualized as a three-layer model:

- Production: What is being produced, and by whom?

- Productivity: How efficiently is that output produced per unit of input?

- Leverage: How does AI change that efficiency ratio and amplify impact?

Each layer builds upon the previous, forming a complete chain from activity → efficiency → impact.

1. Production: Defining the Unit of Output

The foundation of productivity is establishing clarity about what is actually being produced. In manufacturing, this is straightforward: cars, chips, widgets, etc. In knowledge work this is much more challenging, as was discussed above.

To measure AI Value, we must first define the work unit – the atomic unit of value creation – for each team or persona.

The following is a table of examples. Ultimately, the business manager or owner closes to value delivery, whether to customers or to internal stakeholders, must define this work unit.

As we will see in the below examples, the closer the team or persona is to a point of sale, to actual payment by a customer, the easier it is to establish work units of production in quantifiable terms. The further away they are, or the more abstract their work, the more difficult it becomes.

None the less, this ground work must be done to begin to understand the value that AI can deliver.

| Persona | Work Unit (Output) | Description |

| Software Engineer | Feature, service, or bug-free deployment | Code that performs a specific function and passes quality checks |

| Analyst | Report, dashboard, or model | Structured analysis that informs a decision |

| Marketer | Campaign, content piece, or lead generated | Deliverable that drives measurable engagement or conversion |

| Sales Rep | Qualified opportunity or closed deal | Opportunity created or advanced through the funnel |

| Customer Support Agent | Resolved ticket | Issue closed with confirmed customer satisfaction |

By clearly defining what counts as output, enterprises create the foundation for meaningful measurement. Without a clear numerator, all productivity metrics collapse into vanity statistics (e.g., “hours saved”).

2. Productivity: Measuring Output per Unit of Input

Once output is defined, productivity becomes measurable.

At its core:

Productivity = Adjusted Output ÷ Input

Where:

- Adjusted Output = Quantity × Quality × Timeliness

- Input = Time, cost, or man-hours (depending on context)

This definition retains the essence of industrial engineering, output per unit of input, but adapts it for knowledge work by including quality and timeliness adjustments.

Applying this equation to the above table, we could arrive at the following example definitions.

| Persona | Output Metric | Input Metric | Productivity Formula Example |

| Developer | Bug-free features deployed | Developer-hours | (Features × (1 – Bug Rate)) ÷ Hours |

| Analyst | Reports delivered on time | Analyst-hours | (Reports × On-Time Rate) ÷ Hours |

| Marketer | Qualified leads generated | Campaign spend | (Leads × Conversion Quality) ÷ Spend |

| Support Agent | Tickets resolved | Agent-hours | (Resolutions × Satisfaction Score) ÷ Hours |

3. Leverage: Quantifying the AI Multiplier

Leverage is where AI demonstrates its value.

If productivity measures how efficiently work is produced, leverage measures how AI changes that efficiency either by increasing output, improving quality, or reducing required input.

Leverage can be expressed as:

AI Leverage = Productivity_with_AI ÷ Productivity_without_AI

A ratio greater than 1.0 indicates that AI is creating measurable uplift.

But to operationalize this across use cases, we can decompose leverage into three complementary dimensions:

- Adoption: How broadly AI is being used

- % of eligible users or workflows using the AI system

- Example: “60% of analysts used AI copilot this quarter”

- Operating Metric Improvement: How much performance improves

- % improvement in output speed, quality, or accuracy

- e.g., “Average report cycle time decreased by 40%”

- Value Delivered: Aggregate value scaled by adoption

- The total uplift generated across users and workflows

- e.g., (Adoption × Operating Metric Improvement × Volume of Work)

Based on these variables, we can create a composite indicator of AI-driven productivity impact:

AI Value Index (AIVI) = Adoption × (Δ Operating Metric) × Output Volume

This formula mirrors the rigor of industrial engineering, it expresses system-level impact, not anecdotal gains, or generic assumptions about time saved.

It’s the digital equivalent of a factory’s overall equipment effectiveness (OEE), but for knowledge work.

Putting It Into Practice: Measurement Examples by Persona

While the AI Value Framework provides a structured way to measure productivity and leverage, its power becomes clear when applied to specific roles across the enterprise.

Each persona represents a distinct type of knowledge work, with its own definition of output, productivity, and leverage.

By defining these clearly, organizations can move from abstract discussions about “AI efficiency” to quantifiable, comparable impact across functions.

Example 1: Developer Productivity

Software engineering is one of the most visible examples of AI-driven productivity improvement.

AI coding assistants and copilots accelerate code generation, improve quality, and reduce rework, all of which directly influence output per developer-hour.

| Layer | Definition | Metric Example |

| Production | Output defined as “bug-free features deployed” | 25 features released per quarter |

| Productivity | Output per developer-hour | 0.15 features/hour (pre-AI) |

| Leverage | AI-assisted coding increases throughput | 0.25 features/hour (post-AI) → 1.67× leverage |

Decomposition of leverage:

- Adoption = 70% of developers using AI copilot

- Operating Metric Improvement = +40% feature velocity

- Value Delivered = 0.7 × 0.4 × 100 features = 28 additional features per quarter

Beyond raw throughput, AI reduces defects and code review time, improving downstream reliability and team velocity.

The result is a measurable increase in production rate and a compounding improvement in system stability.

Example 2: Analyst Productivity (Reporting & Insights)

Data and business analysts spend significant time gathering, cleaning, and interpreting data before producing insights.

AI copilots and natural language query tools dramatically reduce that friction, allowing analysts to focus on interpretation, not manipulation.

| Layer | Definition | Metric Example |

| Production | Output defined as “decision-quality reports or dashboards delivered” | 40 reports per quarter |

| Productivity | Output per analyst-hour | 0.20 reports/hour (pre-AI) |

| Leverage | AI-assisted data analysis and summarization accelerate delivery | 0.32 reports/hour (post-AI) → 1.6× leverage |

Leverage drivers:

- Adoption = 60% of analysts using AI copilots or NLQ tools

- Operating Metric Improvement = 35% reduction in data prep time

- Value Delivered = 0.6 × 0.35 × 160 reports = 34 reports saved-equivalent per quarter

AI improves not only speed but decision quality. Analysts spend more time interpreting trends and less time cleaning spreadsheets, a higher-value use of human cognition.

Example 3: Sales Productivity (Deal Velocity & Conversion)

Sales productivity depends on timely outreach, personalization, and follow-up. These are activities that AI can dramatically streamline.

AI assistants help reps prioritize leads, draft outreach, and automate CRM updates.

| Layer | Definition | Metric Example |

| Production | Output defined as “qualified deals advanced or closed” | 40 deals advanced per quarter |

| Productivity | Output per sales-hour | 0.10 deals/hour (pre-AI) |

| Leverage | AI-assisted lead scoring and outreach increase deal flow | 0.16 deals/hour (post-AI) → 1.6× leverage |

Leverage drivers:

- Adoption = 65% of sales reps actively using AI assistant

- Operating Metric Improvement = 50% faster lead follow-up

- Value Delivered = 0.65 × 0.5 × 160 deals = 52 additional deals advanced per quarter

AI also improves pipeline hygiene, ensuring more accurate forecasts and better use of management attention.

Sales teams see higher throughput, shorter cycles, and improved close rates without increasing headcount.

Comparing Across Personas

| Persona | Primary Output | Pre-AI Productivity | Post-AI Productivity | AI Leverage (×) |

| Developer | Bug-free features deployed | 0.15 features/hr | 0.25 features/hr | 1.67× |

| Analyst | Reports delivered | 0.20 reports/hr | 0.32 reports/hr | 1.6× |

| Marketer | Campaign assets produced | 0.25 assets/hr | 0.45 assets/hr | 1.8× |

| Sales Rep | Deals advanced | 0.10 deals/hr | 0.16 deals/hr | 1.6× |

| Support Agent | Tickets resolved | 0.80 tickets/hr | 1.20 tickets/hr | 1.5× |

Organizational Roll-Up

When measured across multiple personas, the AI Value Framework enables leaders to compare impact across departments, prioritize use cases, and allocate investment toward the highest-leverage workflows.

This roll-up creates a unified enterprise view of AI productivity, showing, for instance, that a 1.8× leverage in marketing may yield higher revenue per dollar than a 1.6× leverage in sales, depending on relative contribution to business goals.

In practice, organizations can:

- Rank use cases by ROI potential (AI Value Index × Volume × Strategic Importance)

- Identify systemic bottlenecks where AI has the greatest marginal gain

- Establish an enterprise AI Value Dashboard, tracking adoption, leverage, and value delivered over time

This structured, persona-based approach ensures AI investment decisions are guided not by hype or anecdote, but by quantifiable productivity outcomes, transforming AI from a narrative about potential into a disciplined engine of measurable value.

Cohort & Trend Analysis: Measuring Impact Over Time

While one-time measurements of AI productivity gains can demonstrate proof of value, true enterprise impact emerges only when those improvements are tracked over time.

AI adoption, much like industrial automation before it, follows a curve: initial efficiency gains are followed by system-level learning, workflow redesign, and compounding returns.

To capture this dynamic, enterprises must measure both adoption cohorts (who is using AI) and impact trends (how performance evolves over time).

1. Measuring by Cohort: Understanding Adoption Dynamics

A cohort is a group of users, teams, or workflows that began using AI around the same time.

By tracking their productivity metrics longitudinally, organizations can isolate the effects of learning, behavioral change, and organizational diffusion.

Example: Developer Cohorts

| Cohort | Adoption Start | Initial Leverage (Month 1) | Stabilized Leverage (Month 6) | Change Over Time |

| Early Adopters (Pilot Group) | Q1 | 1.35× | 1.75× | +0.40× (29% gain) |

| Mid Adopters (Phase 2 Rollout) | Q2 | 1.20× | 1.55× | +0.35× (29% gain) |

| Late Adopters | Q3 | 1.10× | 1.40× | +0.30× (27% gain) |

This pattern is typical: early adopters achieve higher leverage more quickly, while later cohorts benefit from institutional learning: improved prompts, better workflows, and refined training.

By comparing cohorts, organizations can:

- Identify time-to-value: how long it takes new users to reach peak leverage.

- Quantify learning curves: rate of productivity improvement after AI introduction.

- Diagnose adoption friction: where and why leverage plateaus.

Over time, these analyses reveal which workflows are naturally “AI-ready” and which require process redesign or cultural enablement to capture value fully.

2. Measuring by Trend: Tracking Enterprise Productivity Over Time

Beyond cohorts, enterprises should monitor trend data to understand system-level improvements across departments or personas.

Trends show whether productivity gains are sustained, accelerating, or eroding.

They are also critical for identifying second-order effects such as reduced rework, faster decision cycles, or improved quality that may not appear in initial metrics.

Example: Analyst Productivity Trend (Quarterly View)

| Quarter | AI Adoption (%) | Reports per Analyst-Hour | AI Leverage (×) | Notes |

| Q1 (Pre-AI Baseline) | 0% | 0.20 | 1.00× | Baseline established |

| Q2 (Pilot Launch) | 30% | 0.26 | 1.30× | Early productivity gains observed |

| Q3 (Scaled Rollout) | 65% | 0.31 | 1.55× | Broader adoption across regions |

| Q4 (Full Integration) | 85% | 0.35 | 1.75× | Integration with dashboards, automated reporting |

| Q5 (Continuous Improvement) | 90% | 0.38 | 1.90× | Stable adoption, marginal gains from automation learning |

These trend lines can be visualized through dashboards that track AI Value Index (AIVI) over time: the product of adoption rate × operating metric improvement × output volume.

This enables leadership to see not just individual success stories, but system-wide momentum.

3. Cohort + Trend Analysis Combined: The AI Value Flywheel

Cohort analysis and trend tracking together form a feedback loop and a flywheel of continuous improvement:

- Baseline: Measure current productivity (output ÷ input).

- Pilot (Cohort 1): Deploy AI to a controlled group, track early leverage.

- Analyze & Refine: Identify what drives leverage: process changes, training, or tools.

- Scale: Apply learnings to new cohorts, reducing time-to-value.

- Trend: Track aggregate productivity improvements quarter-over-quarter.

- Feed Back: Use trend data to further refine workflows and AI models.

Over time, this creates compounding leverage, where each new deployment benefits from accumulated institutional knowledge.

This is the digital equivalent of “Kaizen” in industrial engineering: small, continuous improvements that add up to systemic transformation.

4. Visualization: From Point Gains to Cumulative Impact

Enterprises should move beyond static ROI snapshots to cumulative impact charts, showing how AI adoption translates into value creation over time.

For example:

- X-Axis: Time (months or quarters)

- Y-Axis: Cumulative Value Delivered (e.g., features shipped, hours saved, reports delivered)

- Lines: Different personas or departments

These visualizations make it possible to answer strategic questions:

- Which departments are contributing most to enterprise-wide AI leverage?

- What is the slope of improvement (rate of productivity gain)?

- Where is leverage plateauing and why?

A well-instrumented dashboard can surface this data automatically, turning productivity into a living system metric rather than a retrospective report.

5. The Purpose of Longitudinal Measurement

Measuring AI productivity over time serves more than operational tracking; it provides a management system for value creation.

It enables leaders to:

- Prioritize investments in the workflows with the steepest productivity curves.

- Forecast compounding value: predicting when cumulative time saved or output gained will justify further automation investment.

- Create accountability: assigning measurable outcomes to AI initiatives instead of abstract “transformation” goals.

- Identify saturation points: when gains taper, signaling the next frontier for improvement (e.g., process redesign or advanced copilots).

Summary Table: Cohort & Trend Analysis Framework

| Dimension | Purpose | Metric Examples | Time Horizon |

| Cohort Analysis | Compare productivity gains across user groups or adoption phases | Time-to-value, learning rate, leverage delta | Short-to-medium (1–6 months) |

| Trend Analysis | Track system-wide performance over time | AIVI trend, productivity slope, adoption saturation | Medium-to-long (6–24 months) |

| Combined View (AI Flywheel) | Continuous learning and compounding improvement | Rate of leverage acceleration | Ongoing |

In Summary

Cohort and trend analysis transform AI productivity measurement from a static assessment into a dynamic management discipline.

By treating AI adoption as an evolving system rather than a one-time implementation, enterprises can capture not just what AI delivers today, but how its impact compounds tomorrow.

This approach echoes the essence of industrial engineering: continuous measurement, feedback, and improvement, now applied to the invisible workflows of digital, cognitive labor.

It is the final step in converting AI from a collection of isolated tools into a self-improving enterprise operating system.

Conclusion: The Future of Productivity in the Age of AI

For more than a century, industrial engineering provided the foundation for how organizations measured and improved productivity.

It brought discipline, data, and structure to what was once instinct and intuition, transforming factories into finely tuned systems that maximized output per unit of input.

Today, enterprises face an equally profound transition.

The tools of production are no longer machines and materials, but data, models, and cognition. Value is created not by physical throughput, but by the velocity and quality of decisions, insights, and interactions.

And yet, most organizations still measure productivity as if they were operating on a factory floor.

AI changes that.

Artificial intelligence enables the same level of measurement, optimization, and continuous improvement in knowledge work that industrial engineering once enabled in manufacturing.

It makes invisible workflows visible, quantifiable, and improvable.

It allows enterprises to see, for the first time, how digital work actually moves: how decisions are made, how information flows, and where leverage is lost or gained.

The AI Value Framework formalizes this shift.

It reframes productivity in three layers: production, productivity, and leverage. And, it introduces a quantitative way to measure AI’s impact on enterprise performance.

By defining clear outputs, measuring efficiency per input, and quantifying the AI multiplier, organizations can evaluate AI investments with the same rigor they apply to financial performance or supply chain efficiency.

Cohort and trend analysis then elevate this framework from a point-in-time assessment to a living management system.

It tracks adoption, improvement, and compounding returns over time, giving leaders continuous visibility into how AI is reshaping work and where the next gains can be found.

A New Era of Cognitive Industrial Engineering

If the 20th century was defined by mechanical leverage, the 21st will be defined by cognitive leverage.

AI is the new industrial revolution, not because it replaces labor, but because it amplifies human capability through standardization, automation, and continuous learning.

The principles are the same: define, measure, improve.

But the domain has changed from factory floors to digital workflows, from steel to data, from motion to cognition.

In this new era, leaders must think like cognitive industrial engineers. They must design workflows that integrate human judgment and machine intelligence. They must build systems that continuously learn, optimize, and measure improvement.

And they must treat productivity not as a byproduct of technology, but as a discipline: a system to be engineered and managed deliberately.

From Storytelling to Standardization

Enterprises that adopt this mindset will stand apart.

While others rely on narratives about “AI transformation,” they will rely on data. They will be able to demonstrate, with precision, how AI increases leverage per hour, per person, and per dollar. And as their measurement systems mature, they will find that productivity becomes predictable, not anecdotal.

The result is a shift from storytelling about AI value to standardizing it from intuition to instrumentation, from enthusiasm to evidence.

It is the same transformation that industrial engineering brought to manufacturing, now applied to the digital enterprise.

In short:

The organizations that engineer productivity as rigorously as they once engineered production will define the next era of enterprise value creation.

AI does not just make work faster, it makes productivity measurable again.

Want help understanding how to measure AI ROI in your business?